The tattoo universe

The oldest known tattoo has been seen on the Ötzi, a natural mummy, a man who lived in between 3400 BC and 3100 bc. This body was covered with 61 tattoos.

Tattooing was widely used among populations of Taiwan, South China and the Indonesian islands .

Tattoos in western Europe disappeared because of the influence of religion since the pope Adrien and the Jewish religion forbid tattooing. Tattoos were rediscovered by Europeans when James Cook traveled to the south pacific islands.

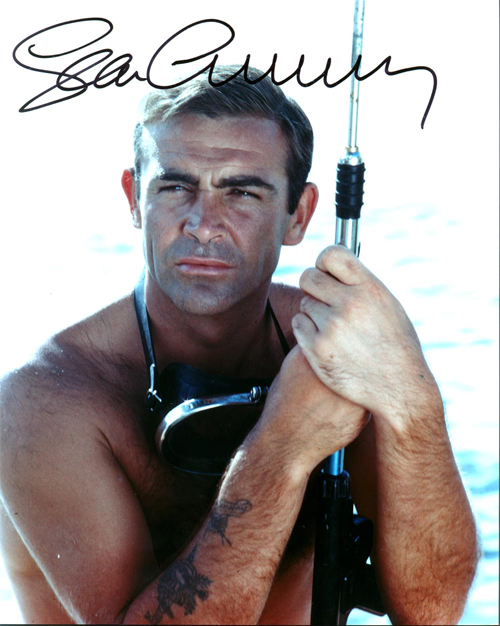

In Europe tattoos were worn mainly by sailors even if numerous personalities such as Nicolas the second, the Russian tsar, or Edward the 7 th or Winston Churchill were tattooed.

The reason behind tattooing were signs of belonging to a group. Some individuals were tattooed against their will, such as prisoners or slaves but a vast majority of individuals tattooed chose to do so.

From the discreet tattoo on the ankle to the imposing figure covering the slightest piece of skin, the tattoo is on all bodies. Once despised, underground, subculture of the street intended for the marginalized, it is now a phenomenon of society.. His practice is however anything but new: we have been able to date it from the time of protohistory, more than 4500 years ago, thanks to the tattooed body of Ötzi, found preserved in the glacier of Hauslabjoch, between Italy and Austria. Tattooing is ancestral, multicultural. This is the reason why its origins are the subject of an exhibition at the Quai Branly, at the Musée des Arts premiers. Before being a popular art, tattooing was a primitive art. Will it soon be part of the « fine art »? For a long time an art on the fringes, forbidden, tattooing is now displayed: on the skin, in the street, in more and more shops, and even in museums. At the Quai Branly, the exhibition « Tattooists, tattooed » invites the public, until October 18, 2015, to discover nearly 300 original works.

In the history of humankind, tattoos have been part of many cultures even since Neolithic times.

More recently in the seventies and even more so in the 90s, tattoos became very fashionable in the western world with music industry leading the way as leaders of opinion of teenagers and young adults.

The tattoo is placed in its historical context. If it is often aesthetic, it is above all ethical, social marker. From one society to another, its function varies: the pe’a, in samoa, is a compulsory initiation rite; in Thailand, the yantra works like a talisman, while in Japan the irezumi is first a punitive tool, before tattooing becomes ornamental in the seventeenth century, then is banned.

L’artiste

Weightless petals and leaves wrap around lithe stems, all inscribed on skin in black linework— Zihwa , a.k.a., Ji Hae Park, is a floral arranger, but her medium is ink. Using her tattoo machine, she creates wispy bouquets that bloom on the body like ivy, sliding over the hip or stretching up the spine, accentuating the natural human form.

Working out of the Reindeer Ink shop in Seoul’s Hongdae district, Hwa is a relative newcomer to the game, and has been working there for since 2015 with her fiance, who inspired her to become a tattooist. “I became his muse and he became mine,” she tells The Creators Project of her jump from graphic design to tattoo art.

Her work is created with a single needle, the thinnest available on market, and she’s grown so comfortable with it that larger needles are more challenging at this point. “I’ve been using it so long that a single needle now feels like a very thin pen,” Zihwa says.

Her style is not exactly divorced from what’s popular in the Korean scene, with other artists working in a similar vein. But she’s particularly laser- focused on black flowers, spreading life in larger and more intricate designs than most. There are also many female tattooists in Korea, where the artform is growing increasingly common and world-renowned. Zihwa says she doesn’t come across many problems being a woman in the tattoo world, but the majority of her clientele are also female.

There’s a bias against tattooing in general, however. It’s actually illegal there and is still taboo with many older Koreans. While there was recently a push to bring it above ground, that seems to have lost traction. So she works to shine a positive, comforting light on the art, making her style counterintuitively political.

“I want to break down the prejudice against tattoos,” Zihwa says. “To express that tattooing is not disgusting.” To do so, she’s leveraging her femininity, and furthering the impact of her work with a portrait series. Soon to be published in book form, the photos are fashioned with floral patterned clothing, wallpapers, and fabrics—not to mention actual flower beds. And they all feature her tattoo style on prominent display, a mix of her ink and temporary tats. “I’m trying to be as feminine as possible.”